“Public safety and preservation of life are the primary duties of any peace officer,” said a former high ranking RCMP executive officer who asked for anonymity out of fear of retaliation by current and former law enforcement officials who are vigilant about any criticism of policing by those in the field. “As far as I can tell, the RCMP did nothing in Nova Scotia to save a life. They weren’t ready. It is embarrassing to me. The entire thing was an epic failure.”

Based upon interviews with other current and former police officers, witnesses, and law enforcement, and on emergency services transcripts, it seems clear that there was a collapse of the policing function on that weekend.

At no point in the two-day rampage did the RCMP get in front of the killer, who the Examiner identifies as GW. It also seems apparent that some Mounties, many of whom were called in from distant locales, were stunningly unaware of the geography and landmarks in the general area as the RCMP tried to keep up with GW.

Sources within the RCMP say a major problem was that communications between various RCMP units was never co-ordinated. “Everyone was on their own channels,” the source said. “Nothing was synchronized. They could have gone to a single channel and brought in the municipal cops as well, but for some reason they didn’t. It was like no one was in charge.”

Nova Scotia RCMP’s chief investigative officer, Chris Leather. Photo: Halifax Examiner.

RCMP Support Services Officer Darren Campbell

As chaotic as the situation might have been for the RCMP, it is evident that the force failed to contain the shooter on the evening of April 18 at the initial multiple crime scenes in the Portapique Beach area of Central Nova Scotia. Thirteen people were murdered that night in which might well be called the first massacre. As has already been acknowledged, the RCMP did not set up roadblocks and perimeters around the area, even though it knew within minutes of arriving at the scene that the shooter was armed and likely on the loose in a replica Mountie police vehicle.

On April 19, the second massacre took place. Unlike the night before, the RCMP knew beforehand who the suspect was, how he was dressed, and what kind of vehicle he was driving, a replica RCMP vehicle. The RCMP had sightings of the killer that morning, but again inexplicably did not seal off roads and highways and try to contain him after numerous 911 calls about sightings. Nine more people, including RCMP constable Heidi Stevenson, were murdered that day.

Preservation of human life is generally accepted to be the ultimate duty of all law enforcement officers in critical incident management. In basic training all Canadian police officers are taught to understand that when confronted with a life-threatening situation, the “priority of life” is demonstrated in this order: hostages, innocent by-standers, police/first responders, and suspects.

The RCMP has said that officers who responded to the original incident employed a tactic known as Immediate Action Rapid Deployment (IARD). With such training, as well-described on-line, the first responding officers are authorized to be proactive and disrupt a crime before criminals become “active shooters.”

“We are taught to move past injured victims and attack the situation,” said one current RCMP member. “If the suspect is in a building, we use a T formation. If he’s outdoors, it’s a diamond. You typically need four officers, but, if need be, you can do it with fewer. The point is to neutralize the suspect as quickly as possible and prevent further injuries or deaths.”

In spite of what the RCMP has publicly stated, law enforcement sources and others have told the Examiner that the first RCMP responders did not actively intervene after arriving at the scene. After discovering a considerable number of slain victims around a property and on or near the road, the officers retreated to a point near the top of Portapique Beach Road where they congregated to wait for reinforcements.

Several RCMP and law enforcement sources say that a corporal from a nearby detachment who was the initial supervisor on the scene froze in place to the distress of other Mounties. The corporal later ran into nearby woods and turned off their flashlight and hid. That officer continues to be off work on stress leave.

Some veteran Mounties say that there were likely a number of factors which caused the first Mounties on the scene to hesitate.

“It could have been inexperience. Maybe there was no backup. And then there’s always that Canada Labour Code thing,” said one long time Mountie.

He was referring to a $550,000 fine imposed on the RCMP in January 2018 for failing to properly arm and train its members after three Mounties were murdered and two injured in a shooting rampage in Moncton on June 4, 2014. Since the Labor Code decision, all RCMP members on patrol are trained in the use assault weapons. Every Mountie carries a Colt C8 rifle with a 30-shot magazine in their patrol cars. The high-powered gun is considered to be an upgrade to the American made AR-15.

“They were in a bad situation,” said the Mountie. ”Their duty is to save lives, but whoever the supervisor was, he or she might have been thinking that they could be criminally sanctioned and go to jail if they send officers into a life threatening situation. At the very least, it could be the end of their career. That’s how the Labour Code fine is interpreted, even if the police are supposed to be exempt from it in the performance of their duties.”

Others have suggested that the RCMP called what has become to be known in policing circles as a FIDO — Fuck it, drive on. What that means is that police deliberately avoid dangerous situations and delay or wait until everything has calmed down before making a move.

Within an hour or so after the first call came in, Staff-Sergeant Allan Carroll took over as the officer-in-charge at a command centre set up in the RCMP detachment at Bible Hill. Sources say that Carroll did not attend the scene and it is not known precisely what he did or didn’t do.

It is noteworthy that his son, Jordan, an RCMP constable, was the second officer to arrive at the scene in Portapique. A knowledgeable source told the Examiner that Staff-Sgt. Carroll retired from the force three weeks ago. A party was held on June 27.

As the Mounties maintained their static position at Portapique Beach Road, tensions were rising. “It was a shit show,” one Mountie said.

Some of the frustrated Mounties wanted to follow their training, move forward and attack the situation. A RCMP tactical officer from Cole Harbour who was called to the scene became frustrated with the fact the Mounties were not attempting to move from their fixed position, save lives and possibly confront the killer. When that Mountie and another said they were going to do it on their own, an unknown supervisor told them: “If you go down there this will be your last shift in the RCMP.” The Mounties held their position.

The RCMP has refused to release its own communications from that night or transcripts of them, but interviews with and transcripts of communications from the nearby Truro Police Department and Emergency Medical Services along with other already noted sources helps fill in some of the gaps and paint a picture of the chaos inside the RCMP.

In the days after the shootings, the RCMP gave three different versions of how long it took the force to respond to the first 911 call which was at 10:01 p.m. First it said officers were on the scene in 12 minutes. On April 21, the RCMP said the first call came in at 10:30 p.m. The next day this was corrected to the call coming in at 10:01 p.m with the first Mounties arriving on the scene at 10:36 p.m.

A local man was driving out of Portapique Beach Road when the killer in his replica cruiser approached him from the other direction and shot at him in his vehicle, wounding him in the arm. According to search warrant documents obtained by the Examiner, that man told investigators he drove up the road and met the cordon of Mounties waiting there. Police sources tell us that the man told Mounties that a man he believed was GW was in a marked police car had shot at him. This occurred sometime after 10:26 p.m. and before 10:35 p.m. when the vehicle was seen leaving the area driving across a field to Brown Loop which is about 200 metres to the east of where the police were positioned.

That man’s report is the first time, as far as we know, that the RCMP were aware that GW was in a recognizable police vehicle.

At or around 10:45 p.m., the killer and his vehicle later are identified as passing by a residence on his way to Debert where he arrived at 11:12 p.m. He parked his car behind a welding shop. He stayed there for six hours.

Until midnight, the fires raged but the RCMP held back the fire department. At least two people were hiding in the woods. One was Clinton Ellison, who had found his brother, Corrie, dead on the road and was stalked by the killer who was using a flashlight to try to find Ellison. The other was GW’s girlfriend, who later said she escaped being handcuffed in the back of another former police vehicle and ran into the woods where she reportedly stayed until 6:30 a.m.

The RCMP put out its first alert to the public on Twitter at 11:32 p.m. It read: “#RCMPNS remains on scene in #Portapique. This is an active shooter situation. Residents in the area, stay inside your homes & lock your doors. Call 911 if there is anyone on your property. You may not see the police but we are there with you #Portapique.”

The RCMP did not alert the two municipal police forces on either side of Portapique, in Truro, 20 minutes away, and Amherst, 45 minutes away. This is significant because in both police forces most of the members have tactical training, a necessity in small departments where any officer could find themselves in a difficult incident without much or any notice. Both police forces had considerable numbers of officers primed and ready to go.

On the Truro Police communications log, at midnight the department received a call from someone at Colchester Regional Hospital reporting that they have a gunshot victim from Portapique and advised that the hospital is in lockdown.

Truro Police Sgt. Rick Hickox called the RCMP six minutes later at 12:06 a.m. looking for an update.

The RCMP returned his call 49 minutes later at 12:55 a.m. to inform the Truro police of an active shooter in Portapique, although GW was long gone from that area.

Three minutes later at 12:58 a.m.: “RCMP dispatch calls advises shooter is associated to a former police car possibly with a decal on it.”

Nine minutes later at 1:07 a.m. the RCMP issued a BOLO (Be on the lookout) for GW as an active shooter and suspect. The RCMP “ID’s some vehicles and girlfriend who is unaccounted for.”

At 1:07 a.m., therefore, the RCMP clearly knew the identity of the suspect and that he had killed many people. The RCMP was not sure about how many because the fires were still raging. Yet the RCMP advised police departments outside the scene to look for this incredibly dangerous person but did not themselves or ask anyone to put up roadblocks and lock down the area. Most importantly, in its tweets the RCMP fudged the markings on the car. The local man who was shot by GW told them it was a police car. The RCMP described it as a former police car with a Canada decal on it. Why the obfuscation?

Informed sources close to the investigation say it was around this time that that an Amherst Police officer was told that the RCMP did not need that force’s assistance because the Mounties had deemed the situation to be a murder-suicide and that the shooter was dead. Amherst Police Chief Dwayne Pike denied in an interview that such a conversation took place. When told about the chief’s denial, the original source persisted in his claim. “Municipal forces like Amherst depend upon the RCMP for lab services,” the source said. “They don’t want to say anything to piss off the Mounties because they will cut them off from the labs. That would cost the locals a lot of money. The RCMP plays rough and the local forces know it, so they keep their mouths shut.”

Chief Pike said recently in an email response from the Examiner that his force was still putting together a timeline of the force’s involvement that weekend.

Back at Portapique Beach, the RCMP continued its investigations at the multiple crime sites. It obtained a search warrant for the killer’s properties at 200 and 287 Portapique Beach Road and 136 Orchard Beach Drive. In the search warrants it cited human remains as one of the things they were looking for.

The RCMP remained silent until 4:12 a.m., when it told Truro police about a Ford F150 truck associated to the suspect. Two minutes later at 4:14 a.m. it updated Truro about another vehicle. Ten minutes later at 4:24 a.m., the RCMP provides a list of vehicles the killer may be driving and noted: “… he is still not in custody.” The RCMP didn’t know where the killer was. They knew he had killed about a dozen people by that time (some victims had not yet been located). But the force did not send out a provincial alert or set up roadblocks around the greater area.

In its communications the RCMP seemed to be suggesting that it was searching for GW, dead or alive, but it still has not done anything proactive to preserve life by obstructing his possible paths, if he were still alive.

In the overnight hours the RCMP says it was busy clearing the various crime scenes in the Portapique Beach area. It is not clear how many Mounties were at the scene or where they came from, although some eventually were called in from New Brunswick. The RCMP has not been clear about any of this, stating that at times there were 30 members there and eventually “100 resources,” whatever that entails. Transfixed as it seemed to be with the nightmarish crime scenes, the force seemed to have put the notion that the killer was alive out of his collective thoughts. No one seems to know what he was doing in Debert.

Some police sources have suggested that GW was perhaps in touch with the RCMP during this period. It is known that a RCMP crisis negotiator was on the scene in Portapique, but Supt. Campbell denied to the CBC in an unpublished interview that the force had any contact with the killer during the overnight period.

While the RCMP was putting out BOLOs as perhaps a hedge, by its actions over the next few hours, the force seemed to be convinced that shooter was no longer a threat. By 6:30 a.m. many of the Mounties on the scene at Portapique, including the staff-sergeant from Bible Hill, were allowed to go home after a long, gruelling night.

Informed sources say that a new incident commander was scheduled to arrive at the scene at 10 a.m., possibly from “the Valley.”

In the interim, the RCMP put out a tweet at 8:02 a.m. reiterating that a shooter was still active in the Portapique area. This made the Truro police anxious. Corporal Ed Cormier immediately called the RCMP at 8:03 a.m. looking for an update. Four minutes later, at 8:07 a.m., the RCMP responded with an updated BOLO, elaborating on their tweet: “[GW] arrestable for homicide. Advises of a fully marked RCMP car Ford Taurus. Could be anywhere in the province. Last seen loading firearms in vehicle. Vehicle photo will be sent when available.”

This information reportedly came from the killer’s girlfriend, who apparently came out of the woods at 6:30 a.m. However, this BOLO provided not much more information than the one at 12:58 a.m., five and a half hours earlier. It added the firearms, but any reader had to presume that GW had firearms in the earlier BOLO since he was described as a “shooter.”

Still, while telling other police agencies that GW “could be anywhere in the province,” so far as the public was told, GW was still in Portapique.

And the RCMP did not engage the local municipal police forces in Truro, Amherst, the New Glasgow area or even Halifax, an hour away. There are more than 900 Mounties employed in Nova Scotia in various capacities. Only a relative few of them were called in. The Mounties, however, did enlist the help of RCMP members in New Brunswick from Moncton and as far away as Fredericton, a three-hour drive at speed from Portapique.

One

of four H125 helicopters used by the Nova Scotia Department of Natural

Resources. Photo: Communications Nova Scotia (CNW Group/Airbus)

“The RCMP has nine helicopters across the country, but as far as I know has never had one in Nova Scotia,” said a former executive level RCMP officer in an interview. “In renewing its contracts with the RCMP, it appears that the government of Nova Scotia has taken the position that a helicopter is an unneeded frill and dispensed with the idea. That was a big mistake. The questionable leadership of the RCMP and the questionable leadership of the government of Nova Scotia has failed to appreciate the changing dynamics of policing. The force needed a helicopter that weekend and didn’t have one. Twenty-two people died. Some of those lives could have been saved.”

Until 2001, the RCMP had an agreement with the provincial Department of Natural Resources, which commands four helicopters. In return, informed sources say, the DNR was allowed to use the RCMP’s forensic laboratories. The RCMP denied that use in 2001, so the DNR stopped allowing the RCMP the use of the helicopters.

In the intervening 19 years, whenever the RCMP required the use of a helicopter it either negotiated with the armed forces or it paid private rental companies for one.

The relaxed attitude of the RCMP in the early morning hours of Sunday was evidenced in a video shot by CBC at the RCMP command centre at the firehall in Great Village. Emergency response team members stand in a circle chatting away. A bored Mountie wielding a C8 rifle paces back and forth. Another Mountie helps local fire-fighters roll up some hose.

After this, things began to get even hairier.

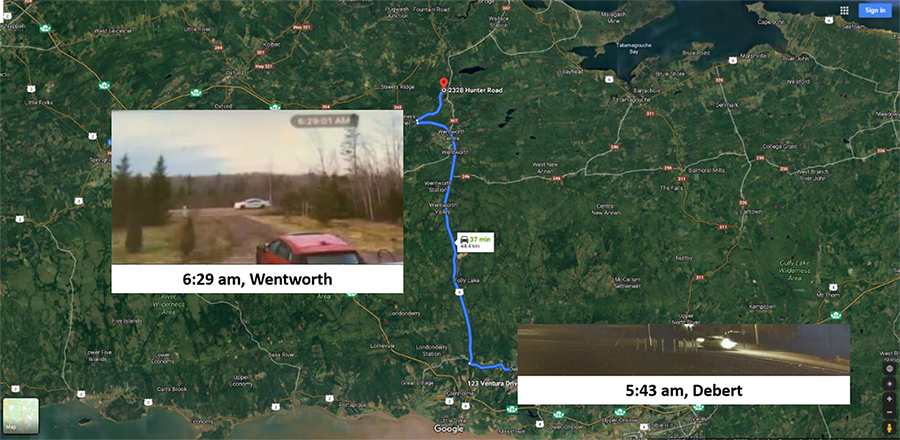

An

RCMP map shows GW’s route from 123 Ventura Drive in Debert to 2328

Hunter Road, Wentworth. Insets of still images taken from different

videos show GW’s replica police car at 5:43am in Debert and passing a

driveway on Hunter Road in Wentworth at 6:29am.

For some unknown reason, the killer lingered at the McLeod property for three hours. At some point he set the house on fire and left at 9:35 a.m. according to a security camera. It is not yet known what he was doing while he lingered there.

Lillian Hyslop. Photo: Facebook.

The RCMP flooded the area and thought it had the killer contained, even though callers to 911 had told them that he had been seen heading eastbound on Highway 4 toward Truro. Thinking it had the killer trapped, the RCMP again failed to mobilize in an attempt to find, stop or capture him. As it had in Portapique, the RCMP did not call for help from other forces, did not set up roadblocks, call for a helicopter or track, contain or attack GW.

Instead of calling in local police for help, the Mounties relied on their own, some from far away who were entirely unfamiliar with the territory and couldn’t find roads. One couldn’t find the RCMP building in Bible Hill just outside Truro. Another indicated to a Truro police dispatcher that he didn’t realize that there was a hospital in Truro.

Further evidence of the communications disconnect between Mounties and their commanders and between Mounties and other police forces was how messages about what was going on in Wentworth were disseminated.

At 9:46 a.m., a RCMP officer at the Colchester Regional Hospital told Truro Constable Cormier that the force believed it had the killer pinned down in Wentworth. Two minutes later Truro Constable Thomas Whidden reported that that he had heard informally from the RCMP that the killer was headed to Truro. The RCMP was not formally engaging the Truro Police.

Then, at 10 a.m., RCMP Chief Supt. Chris Leather, the number two Mountie in the province and the chief of criminal operations, further added to the ball of confusion. He sent an e-mail to Truro Police Chief Dave McNeil that the RCMP had the shooter pinned down in Wentworth. But that wasn’t true. What Leather later told reporters is that he had meant to Onslow, 30 kilometres to the south of Wentworth, an 8-minute or so drive west of Truro.

By now the killer was heading back to the Debert area where he had spent the overnight parked behind a garage in the industrial park. Despite the fact that 13 people had been murdered, just west of there in Portapique, there were still no roadblocks or impediments to his travel.

At 9:48 a.m., GW visited the house of a couple he knew who lived on the 2900 block of Highway 4, in Debert, just north of the intersection with Highway 104. The couple hid under their bed, a gun cocked and ready. The killer backed off and continued moving south. GW left without harming them, and the couple called 911.

At 10:04 a.m. the RCMP sent out a tweet asking people to avoid the Hidden Hilltop Campground in Glenholme, which is near the couple’s home. But GW wasn’t there. He had moved on to Plains Road in Debert, where he killed Heather O’Brien and Kristen Beaton, two Victorian Order of Nurses who were driving in separate cars. The RCMP later said that the killer pulled them over and later still corrected that statement, saying he hadn’t. The force has yet not explained what really happened.

Near Onslow, the killer passed a Mountie who was driving the other way. The unnamed Mountie thinking that he had just seen the suspect is reported to have turned around to pursue him, but lost sight of the killer. There was no RCMP back up in the area.

Although the killer had been spotted, the RCMP did not issue a province wide alert or take any action to impede or stop the killer with the ultimate intention of preserving life.

The killer then headed to Truro where he drove down Walker, Esplanade, and Willow streets between 10:16 and 10:19 a.m. and then headed south out of town toward Brookfield. The Truro police were entirely unaware that he had done that until video surfaced later that week.

Meanwhile, the RCMP finally had negotiated the use of a helicopter from the Department of Natural Resources. A source close to the DNR said that department was told that the helicopter would be used to scout the Portapique Beach Road fire scenes to ensure that the fires had not spread into the woods. The helicopter with a Mountie on board took off for Portapique. The pilot was never instructed to hunt for the killer in his readily identifiable mock RCMP cruiser — it was the only one on the road in the area that featured a push bar or ram package over its front bumper.

Back in the Truro area, more than 12 hours since the first alarm went in at Portapique Beach Road, the RCMP were still playing catch-up. At 10:21 a.m., the force tweeted that GW was in the Central Onslow and Debert area “in a vehicle that may resemble what appears to be an RCMP vehicle & may be wearing what appears to be an RCMP uniform.” By then, he was long gone, but the tweet or whatever else the RCMP was saying in its internal communications may well have provoked one of the strangest known incidents that day.

The Onslow Belmont Fire Hall. Photo: Jennifer Henderson

The killer was well on the other side of Truro by then.

Five minutes earlier, at 10:25 a.m., in a well-known security video, the killer pulled into the lot of a business in Millbrook, got out of the car and changed out of a RCMP jacket into a yellow vest. He got back in the car and headed south toward Shubenacadie where two RCMP constables, Chad Morrison and Heidi Stevenson were driving in separate vehicles to meet up near the intersection of Highway 2 and 224.

Ten minutes after changing into the vest, the killer pulled up beside Const. Morrison who was waiting by the side of the road for Const. Stevenson. He fired into the car, striking Morrison in one hand and the other arm.

Morrison apparently radioed for help, but the media have not been privy to that communication.

A Nova Scotia EHS tape, widely circulating on the Internet, indicates that at around the time shortly after Morrison was shot and paramedics responded. In the conversation with a dispatcher, a paramedic described a “member” (the common term for a Mountie) who was shot in the foot. The paramedic says he can’t transport the patient to hospital yet because he first had to recover a gun the officer had left in the woods and lock his police car. The RCMP has not confirmed any of this.

At 10:48 a.m., the killer slammed his vehicle into that of Const. Stevenson at the traffic circle connecting highways 2 and 224. The RCMP says Stevenson “engaged” the killer, but witnesses say he shot at her through the windshield and then dragged her out of her damaged vehicle. He then executed her with multiple shots as she lay on the pavement. He set his and Stevenson’s vehicles on fire. When a passerby, Joey Webber, stopped to help, he was killed. The killer then dragged his guns and paraphernalia to Webber’s Chevy Tracker and drove off.

After the shootings were reported, the RCMP still did not try to get in front of the killer and stop him.

- Gina Goulet

- Joey Webber

The RCMP, meanwhile, was now looking for GW in Joey Webber’s Chev Tracker, issuing a Tweet to that effect at 11:24 a.m.

Unfortunately, for the killer, Goulet’s vehicles gas tank may have been empty. That seems a likely reason why he pulled into the Irving Station at Endfield; or, perhaps, he felt the gathering police presence around him. Instead of blocking off roads, the RCMP was going to businesses such as Sobeys and asking them to close their doors.

It was around this time that Halifax Police became engaged and began to set up a roadblock at exit 5A on Highway 102 heading into Halifax, one exit south of the airport. The Halifax Examiner previously reported another curiosity about the lookout for the killer in that Halifax Police Chief Dan Kinsella apparently ordered his officers to attempt to capture the killer and not shoot him.

Whatever the case, suspect was in his vehicle at the Irving station when a Mountie, reportedly a canine officer, who was stopped to fill up his vehicle recognized him. A brief confrontation ensued and the shooter was killed.

Meanwhile, the Department of Natural Resources helicopter was done with its reconnaissance of the Portapique crime scenes and was returning to Halifax. In the distance, the black smoke from the two burning cars at the traffic circle. Sources say they pilot was never engaged to try and hunt down the killer.

Obviously operating on a different frequency than other Mounties, the pilot was informed that the suspect was down at the Irving Station at Exit 7 on the 102.

As he landed in a field near the station to let off the Mountie who was with him, the pilot received a transmission from a gruff sounding RCMP Officer who identified himself as being “the RCMP Command Post.”

What the Mountie had to tell him was that the suspect had been brought down at the Irving Station in Enfield “at Exit 11.”

Exit 11, as it turns out, is in Stewiacke, approximately 43 kilometres to the north.

It was a fitting end to an epic policing failure.

https://www.halifaxexaminer.ca/featured/an-epic-failure-the-first-duty-of-police-is-to-preserve-life-through-the-nova-scotia-massacre-the-rcmp-saved-no-one/?fbclid=IwAR0_j4vWJgQzOADWvT1k9gPWqagWguJOovsGGd34Oo435r393M6RwH310Ls

Please share this.

No comments:

Post a Comment