Marilyn and Her Monsters

For all the millions of words she has inspired, Marilyn Monroe remains something of a mystery. Now a sensational archive of the actress’s own writing—diaries, poems, and letters—is being published. With exclusive excerpts from the book, Fragments, the author enters the mind of a legend: the scars of sexual abuse; the pain of psychotherapy; the betrayal by her third husband, Arthur Miller; the constant specter of hereditary madness; and the fierce determination to master her art.

MONROE DOCTRINE

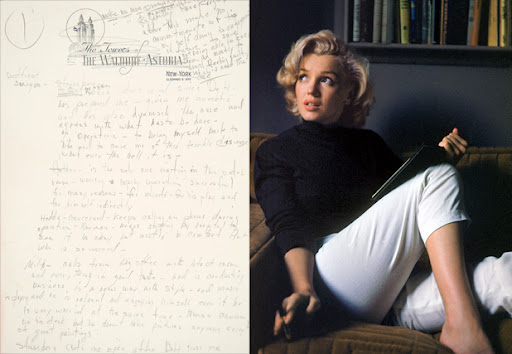

A dream record by Marilyn Monroe from 1955, when she lived at the Waldorf-Astoria, in Manhattan. Photograph, right, from Time & Life Pictures/Getty Images.

Excerpted from Fragments: Poems, Intimate Notes, Letters by Marilyn Monroe, edited by Stanley Buchthal and Bernard Comment, to be published October 12th by Farrar, Straus and Giroux, LLC (US), HarperCollins (Canada and UK); © 2010 by LSAS International, Inc.

She was always late for class, usually arriving just before they closed the doors. The teacher was strict about not entering in the middle of an exercise or, God forbid, in the middle of a scene. Slipping in without makeup, her luminous hair hidden under a scarf, she tried to make herself inconspicuous. She usually took a seat in the back of one of the dingy rooms in the Malin Studios, on 46th Street, smack in the middle of the theater district. When she raised her hand to speak, it was in a tiny wisp of a voice. She didn’t want to draw attention to herself, but it was hard for the other students not to know that the most famous movie star in the world was in their acting class. A few blocks away, above Loew’s State Theater, at 45th and Broadway, there was the other Marilyn—the one everyone knew—52 feet tall, in that infamous billboard advertising Billy Wilder’s The Seven Year Itch, a hot blast from the subway grating causing her white dress to billow up around her thighs, her face an explosion of joy.

When it was her turn to do an acting exercise focusing on sense memory, Marilyn took the floor in front of a small group of students. She was asked to remember a moment in her life, to recall the clothes she was wearing, to evoke the sights and smells of that memory. She described how she had felt about being alone in a room, years before, when an unnamed man walked in. Suddenly, her acting teacher admonished her, “Don’t do that. Just tell us what you hear. Don’t tell us how you feel.” Marilyn began to cry. Another student, an actress named Kay Leyder, recalled, “As she described her clothes … what she heard … the words that were said to her … she began crying, sobbing, until at the end of it she was really devastated.” Was this the real Marilyn Monroe: an insecure, shy, 29-year-old woman?

A handwriting expert takes a magnifying glass to Marilyn’s script, scrutinizing its deeper meaning.

Marilyn left the archive, along with all her personal effects, to her acting teacher Lee Strasberg, but it would take a decade for her estate to be settled. Strasberg died in February 1982, outliving his most famous student by 20 years, and in October 1999 his third wife and widow, Anna Mizrahi Strasberg, auctioned off many of Marilyn’s possessions at Christie’s, netting over $13.4 million, but the Strasbergs continue to license her image, which brings in millions more a year. The main beneficiary is the Lee Strasberg Theatre & Film Institute, on 15th Street off Union Square, in New York City. It is, you might say, the house that Marilyn built.

Several years after inheriting the collection, Anna Strasberg found two boxes containing the current archive, and she arranged for the contents to be published this fall around the world—in the U.S. as Fragments: Poems, Intimate Notes, Letters by Farrar, Straus and Giroux. The archive is a sensational discovery for Marilyn’s biographers and for her fans, who still want to rescue her from the taint of suicide, from the accusations of tawdriness, from the layers of misconceptions and distortions written about her over the years. Now at last we have an unfiltered look inside her mind.

“I picked up a chair and slammed it ...against the glass. It took a lot of banging. I went over with the glass concealed in my hand and sat.”

“Complete Subjection, Humiliation, Alonement”

Marilyn began taking private lessons with celebrated acting teacher Lee Strasberg in March 1955, encouraged by the acclaimed theater and movie director Elia Kazan, with whom she had had an affair. “Kazan said I was the gayest girl he ever knew,” she wrote to her analyst Dr. Ralph Greenson in the last and perhaps the most important letter found in this archive, “and believe me he has known many. But he loved me for one year and once rocked me to sleep one night when I was in great anguish. He also suggested that I go into analysis and later wanted me to work with his teacher, Lee Strasberg.”She was living at the Gladstone Hotel, on 52nd Street off Park Avenue, when she began working with Strasberg and embarked upon the psychoanalysis that was de rigueur for taking classes at the Actors Studio. Founded in 1947 by Kazan and directors Cheryl Crawford and Robert Lewis, it was the holy temple of the Method—acting exercises and scenes that focused on sense memories and “private moments” dredged from the actor’s life. Throughout the late 1940s and through much of the 1950s and 1960s, the Actors Studio was the most revered laboratory for stage actors in America. Its membership (one was not officially a “student” but a “member”) included a roster of the most compelling actors of the day: Marlon Brando, James Dean, Montgomery Clift, Julie Harris, Martin Landau, Dennis Hopper, Patricia Neal, Paul Newman, Eli Wallach, Ben Gazzara, Rip Torn, Kim Stanley, Anne Bancroft, Shelley Winters, Sidney Poitier, Joanne Woodward—who all brought those techniques into film.

Strasberg, born in 1901 in Austria-Hungary and raised on the Lower East Side of Manhattan, was a genius at analyzing an actor’s performance and a stern and often cold taskmaster. Short, bespectacled, and intense, he wasn’t, recalled Ellen Burstyn, “one for small talk.” For Marilyn, who grew up shunted from one foster family to another, not knowing who her father was, he became a beloved paternal figure, autocratic yet nurturing, and his acceptance of her as a private student bolstered her confidence and gave her the training to improve her acting, and turned her from a movie star (and punch line) into a true artist. But years later Kazan observed, “The more naïve and self-doubting the actors, the more total was Lee’s power over them. The more famous and the more successful these actors, the headier the taste of power for Lee. He found his perfect victim-devotee in Marilyn Monroe.”

Most important, this archive, far more deeply than the Inez Melson collection, made public in V.F. in October 2008, reveals a woman in search of herself, undergoing the harrowing experience of psychoanalysis for the first time, at the urging of Strasberg. The key players include Strasberg himself, her three psychiatrists—Dr. Margaret Hohenberg, Dr. Marianne Kris, and Dr. Ralph Greenson—and her third husband, Arthur Miller, whom she confesses to loving body and soul, but by whom she ultimately felt betrayed. These poems, musings, dreams, and correspondence also touch on her great fear of displeasing others, her chronic lateness, and three of the biggest traumas of her shortened life: one buried in her past, and two that took place a few years after she began studying with Strasberg. But they also reveal her growth both as an artist and a woman as she manages to cope with memories and disappointments that threatened to overwhelm her.

In a five-and-a-half-page typed document, Marilyn looked back on her early marriage to James Dougherty, an intelligent, attractive man five years her senior. They married on June 19, 1942, when she was just 16, and in this document she describes her feelings of loneliness and insecurity in that hastily agreed-to union, which was less of a love match than a way to keep Marilyn—then Norma Jeane Baker—out of the orphanage when her caretakers at the time, Grace and Erwin “Doc” Goddard, moved away from California. (There has also been speculation that Grace wanted to remove Norma Jeane from her husband’s too appreciative eye.)

Marilyn was not technically orphaned, as her mother, Gladys Monroe Baker, outlived her famous daughter, but because Gladys was a schizophrenic who spent years in and out of psychiatric hospitals, Marilyn was virtually abandoned, raised by various foster families and by Grace Goddard, a close friend of her mother’s. There were nearly two years when Marilyn was parked in an orphanage. Dougherty liked the idea of rescuing the shy, pretty girl, who left high school to marry him. Not surprisingly, the union failed, and they divorced on September 13, 1946.

“My relationship with him was basically insecure from the first night I spent alone with him,” she wrote in this long, undated, somewhat rambling memoir of that marriage, probably written by hand after undergoing analysis and later typed by her personal assistant, May Reis; the archivists suggest it was written when Norma Jeane was 17 and still married to Dougherty, but the emphasis on self-analysis seems to place it later in her life. It’s an intriguing document, peppered with misspellings, weaving the past with the present, at times reliving scenes from the marriage and her jealousy of Dougherty, at times stepping back and analyzing her emotional state of mind. She wrote,

Her memory of that marriage revolves around her fear that Dougherty preferred a former girlfriend, probably Doris Ingram, a Santa Barbara beauty queen, which triggered Marilyn’s sense of unworthiness and vulnerability to men:

My first impulse then was one of complete subjection humiliation, alonement to the male counterpart. (all this thought & writting has made my hands tremble …

Its not to much fun to know yourself to well or think you do—everyone needs a little conciet to carry them through & past the falls.

“Best Finest Surgeon—Strasberg to Cut Me Open”

Included in the archive are several black “Record” notebooks—the slim, narrow, leather-bound diaries then favored by writers. The earliest of these notebooks begins with the words “Alone!!!!!!! I am alone I am always alone no matter what” in a slender, cursive script that leans dangerously forward, as if about to fall off a cliff.Marilyn apparently began recording her thoughts around 1951. Two years prior, broke and desperate, she had posed nude for photographer Tom Kelley, for a calendar series. After she signed a new contract with Fox, in December 1950, and the calendar photos surfaced, Marilyn deflected criticism by saying she had taken the job because “I was hungry.” The public forgave her. She possessed a quality that seemed to trigger rescue fantasies in men and women alike, even before the sad details of her fractured childhood were completely known. In part, Marilyn knew that to cast herself as an orphan stirred up pity and empathy.

By Christmas of 1954, she was living in New York City. She had already appeared in Niagara and Gentlemen Prefer Blondes, where she perfected her signature character, the vulnerable, “dumb,” sensual blonde, and, in How to Marry a Millionaire, with brilliant success. After that, Monroe’s fame was such that she supplanted in popularity the ultimate World War II pinup girl, Betty Grable, who shortly left Fox and bequeathed the largest dressing room on the lot to Marilyn. She had married Joe DiMaggio in January of that year, entertained troops in Korea, and filmed The Seven Year Itch. But the movie’s famous billboard displeased the puritanical “Yankee Clipper,” and the two filed for divorce in October, just nine months after marrying.

Encouraged by Strasberg, Marilyn began seeing Dr. Margaret Hohenberg as often as five times a week, first at Marilyn’s rooms at the Gladstone Hotel, then at Dr. Hohenberg’s office, at 155 East 93rd Street. The psychiatrist, an acquaintance of Strasberg’s, was a Brünnhilde type, a 57-year-old Hungarian immigrant complete with tightly wound braids and a Valkyrian bosom. Strasberg strongly believed that Marilyn needed to open up her unconscious and root through her troubled childhood, all in the service of her art. Between her sessions with Strasberg and with Dr. Hohenberg, she began recording some of those raked-up memories, including a devastating incident of sexual abuse. Described around 1955, in an Italian notebook whose pages are lined and numbered in green, this memory fully emerges, with the humiliating aftermath of being punished by her great-aunt Ida Martin, a strict, evangelical Christian paid by Grace Goddard to look after Norma Jeane for several months from 1937 to 1938. (Could this have been the sense-memory exercise that left her weeping in Strasberg’s acting class?) Marilyn wrote,

been obeying her—

it’s not only harmful

for me to do so

but unrealality because

life starts from Now

have set for myself)

On the stage—I will

not be punished for it

or be whipped

or be threatened

or not be loved

or sent to hell to burn with bad people

feeling that I am also bad.

or be afraid of my [genitals] being

or ashamed

exposed known and seen—

so what

or ashamed of my

sensitive feelings—

to cut me open which I don’t mind since Dr. H

has prepared me—given me anaesthetic

and has also diagnosed the case and

agrees with what has to be done—

an operation—to bring myself back to

life and to cure me of this terrible dis-ease

whatever the hell it is—

Strasberg is

deeply disappointed but more even—

academically amazed

that he had made such a mistake. He

thought there was going

to be so much—more than he had ever

dreamed possible …

instead there was absolutely nothing—

devoid of

every human living feeling thing—

the only thing

that came out was so finely cut sawdust—like out of a raggedy ann doll—and the sawdust

spills

all over the floor & table and Dr. H is

puzzled

because suddenly she realizes that this is a

new type case. The patient … existing

of complete emptiness

Strasberg’s dreams & hopes for theater

are fallen.

Dr. H’s dreams and hopes for a permanent

psychiatric cure

is given up—Arthur is disappointed—

let down +

Marilyn was re-introduced to the acclaimed playwright at the producer Charles Feldman’s home. Feldman had produced The Seven Year Itch, a huge success, and Marilyn had returned to Hollywood in February of 1956 to begin work on Bus Stop, directed by Josh Logan. She was instantly smitten by the Pulitzer Prize—winning author of All My Sons, Death of a Salesman, The Crucible, and A View from the Bridge, who was still married to his first wife, Mary Slattery, at the time. Miller possessed those traits she most admired: intellectual and artistic achievement, high seriousness. They wed in a civil ceremony on June 29, 1956, Marilyn having converted to Judaism. Two days later, Lee Strasberg acted as her father, giving the bride away in an intimate Jewish wedding.

At first, she was deliriously happy, moving back to New York with her new husband to take up residence in her dazzlingly white apartment at 2 Sutton Place, to which she had moved after leaving the Waldorf-Astoria, and then on to 444 East 57th Street, in an apartment with a book-lined living room, complete with fireplace and piano. In the Italian, green, engraved diary, she wrote,

about protecting Arthur

I love him—and he is the

only person—human being I have

ever known that I could love not only

as a man to which I am attracted to

practically

out of my senses about—but he [is] the only

person … that I trust as

muchas myself—because when I do trust my-

self (about certain things) I do fully

Marilyn writes of her early sexual abuse: “I will not be punished for it or be whipped or be threatened or not be loved or sent to hell to burn.”

They were probably happiest in the summer of 1957, spent in a rented house in Amagansett, on Long Island, where they swam and took long walks on the beach. She looks especially radiant in photographs from this era, when she happily entered into Miller’s world—for example, attending a luncheon given by the novelist Carson McCullers for the writer Isak Dinesen. Marilyn was gay and witty in this company, easily holding her own—her vitality and innocence reminded Dinesen of a wild lion cub. She became friends with writer Truman Capote and met some of her literary heroes, such as poet Carl Sandburg and novelist Saul Bellow, with whom she dined at the Ambassador Hotel on the occasion of the Chicago premiere of Some Like It Hot. Bellow was bowled over by her.Several photographs taken of Marilyn earlier in her life—the ones she especially liked—show her reading. Eve Arnold photographed her for Esquire magazine in a playground in Amagansett reading James Joyce’s Ulysses. Alfred Eisenstaedt photographed her, for Life, at home, dressed in white slacks and a black top, curled up on her sofa, reading, in front of a shelf of books—her personal library, which would grow to 400 volumes. In another photograph, she’s on a pulled-out sofa bed reading the poetry of Heinrich Heine.

If some photographers thought it was funny to pose the world’s most famously voluptuous “dumb blonde” with a book—James Joyce! Heinrich Heine!—it wasn’t a joke to her. In these newly discovered diary entries and poems, Marilyn reveals a young woman for whom writing and poetry were lifelines, the ways and means to discover who she was and to sort through her often tumultuous emotional life. And books were a refuge and a companion for Marilyn during her bouts of insomnia.

In one of the handful of sweet and affecting poems included in this archive, Marilyn, still in the first flush of her love for Miller and imagining what he might have been like as a young boy, wrote a poem about him:

in the faint light—I see his manly jaw

give way—and the mouth of his

boyhood returns

with a softness softer

its sensitiveness trembling

in stillness

his eyes must have look out

wonderously from the cave of the little

boy—when the things he did not understand—

he forgot

oh unbearable fact inevitable

yet sooner would I rather his love die

than/or him?

“Ah Peace I Need You—Even a Peaceful Monster”

But after she and Miller traveled to England for four months for the filming of The Prince and the Showgirl, with Laurence Olivier, things began to sour. They moved into a magnificent manor called Parkside House, in Surrey, outside of London. On paper, it was an idyll: here she was producing a film directed by and starring one of the most respected actors of his generation, and living in a grand country house with the man she most loved. She couldn’t have felt more fulfilled and vindicated as an artist, until a chance discovery undermined her fragile confidence in herself and her trust in her husband. It was at Parkside House that Marilyn stumbled upon a diary entry of Miller’s in which he complained that he was “disappointed” in her, and sometimes embarrassed by her in front of his friends.Marilyn was devastated. One of her greatest fears—that of disappointing those she loved—had come true. His betrayal confirmed what she’d “always been deeply terrified” of: “To really be someone’s wife since I know from life one cannot love another, ever, really,” as she wrote in another “Record” journal entry.

After this discovery, Marilyn found it so difficult to work that she flew in Dr. Hohenberg from New York. She was having trouble sleeping, relying on barbiturates. On Parkside House stationery, she wrote one night after Miller had gone to bed:

comes/reappears the shapes of monsters

my most steadfast companions …

and the world is sleeping

ah peace I need you—even a

peaceful monster.

That winter Miller worked on adapting one of his short stories for the screen, “The Misfits,” while Marilyn grappled with her feelings of disappointment and loss:

In every spring the green [of the ancient maples] is too sharp—though the delicacy in their form is sweet and uncertain—it puts up a good struggle in the wind—trembling all the while… I think I am very lonely—my mind jumps. I see myself in the mirror now, brow furrowed—if I lean close I’ll see—what I don’t want to know—tension, sadness, disappointment, my [“blue” is crossed out] eyes dulled, cheeks flushed with capillaries that look like rivers on maps—hair lying like snakes. The mouth makes me the sadd[est], next to my dead eyes…

When one wants to stay alone as my love (Arthur) indicates the other must stay apart.

Help

I feel life coming closer

when all I want

Is to die.

Scream—

You began and ended in air

but where was the middle?

“I have always been deeply terrified to really be someone’s wife since I know from life one cannot love another, ever, really.”

Sept. 9

—Remember, somehow, how—

Mother always tried to

get me to “go out” as

though she felt I

were too unadventurous.

She wanted me even

to show a cruelty

toward woman. This

in my teens. In return,

I showed her that I

was faithful to her.

Miller completed his screenplay for The Misfits, with the central role of a wounded young woman, who falls in love with a much older man, based, not surprisingly, on Marilyn. In July of 1960, filming began in the Nevada desert, under John Huston’s direction, with Marilyn, Clark Gable, Montgomery Clift, Thelma Ritter, and Eli Wallach in key roles. Miller was on location, watching as his wife began to unravel in the blistering heat. On the set he met and fell in love with a photographic archivist on the film, Inge Morath, who would become his third wife. On November 11, 1960, Marilyn and Arthur Miller’s separation was announced to the press.

Three months later, back in New York, emotionally exhausted and under Dr. Kris’s care, Marilyn was committed to Payne Whitney’s psychiatric ward. What was supposed to have been a prescribed rest cure for the overwrought and insomniac actress turned out to be the most harrowing three days of her life.

Kris had driven Marilyn to the sprawling, white-brick New York Hospital—Weill Cornell Medical Center, overlooking the East River at 68th Street. Swathed in a fur coat and using the name Faye Miller, she signed the papers to admit herself, but she quickly found she was being escorted not to a place where she could rest but to a padded room in a locked psychiatric ward. The more she sobbed and begged to be let out, banging on the steel doors, the more the psychiatric staff believed she was indeed psychotic. She was threatened with a straitjacket, and her clothes and purse were taken from her. She was given a forced bath and put into a hospital gown.

On March 1 and 2, 1961, Marilyn wrote an extraordinary, six-page letter to Dr. Greenson vividly describing her ordeal: “There was no empathy at Payne-Whitney—it had a very bad effect—they asked me after putting me in a ‘cell’ (I mean cement blocks and all) for very disturbed depressed patients (except I felt I was in some kind of prison for a crime I hadn’t committed. The inhumanity there I found archaic … everything was under lock and key … the doors have windows so patients can be visible all the time, also, the violence and markings still remain on the walls from former patients.)”

“Peter He Might Harm Me, Poison Me”

A psychiatrist came in and gave her a physical exam, “including examining the breast for lumps.” She objected, telling him that she’d had a complete physical less than a month before, but that didn’t deter him. After being unable to make a phone call, she felt imprisoned, and so she turned to her actor’s training to find a way out: “I got the idea from a movie I made once called ‘Don’t Bother to Knock,’ ” she wrote to Greenson—an early film in which she had played a disturbed teenage babysitter.When she refused to cooperate with the staff, “two hefty men and two hefty women” picked her up by all fours and carried her in the elevator to the seventh floor of the hospital. (“I must say that at least they had the decency to carry me face down.… I just wept quietly all the way there,” she wrote.)

She was ordered to take another bath—her second since arriving—and then the head administrator came in to question her. “He told me I was a very, very sick girl and had been a very, very sick girl for many years.”

Dr. Kris, who had promised to see her the day after her confinement, failed to show up, and neither Lee Strasberg nor his wife, Paula, to whom she finally managed to write, could get her released, as they were not family. It was Joe DiMaggio who rescued her, swooping in against the objections of the doctors and nurses and removing her from the ward. (He and Marilyn had had something of a reconciliation that Christmas, when DiMaggio sent her “a forest-full of poinsettias.”)

It should be noted that this is one of the few letters that have already seen the light of day. It was quoted almost in its entirety in Donald Spoto’s Marilyn Monroe: The Biography, published in 1993. Spoto says he got it from the estate of May Reis—Marilyn’s personal assistant from the 1950s until her death—who had typed the letter and kept a copy. Nonetheless, it is fascinating to be able to read the facsimile of this long-sought-after document and to see some of the elements left out of Spoto’s book, such as an intriguing postscript that reads:

From Yves [Montand] I have heard nothing—but I don’t mind since I have such a strong, tender, wonderful memory.

I am almost weeping.

Even with the revelations and unexpected pleasures of this soon-to-be-published archive, the deep mystery of her death remains. For those who believe that Marilyn’s death was indeed a suicide, there are many indications of her emotional fragility and a description of a past suicide attempt. “Oh Paula,” she wrote in an undated note to Paula Strasberg, “I wish I knew why I am so anguished. I think maybe I’m crazy like all the other members of my family were, when I was sick I was sure I was. I’m so glad you are with me here!”

For those who believe she died of an accidental overdose, mixing prescribed barbiturates with alcohol, the archive contains evidence of her optimism, her feeling that she has come to rely on herself and will solve her problems through work and her capable, businesslike plans for the future.

about being afraid

of Peter he might

harm me,

poison me, etc.

why—strange look in his eyes—strange

behavior

in fact now I think I know

why he’s been here so long

because I have a need to

be frighten[ed]—and nothing really

in my personal relationships

(and dealings) lately

have been frightening me—except

for him—I felt very uneasy at different

times with him—the real reason

I was afraid of him—is because I believe

him to be homosexual—not in the

way I love & respect and admire [Jack]

who I feel feels I have talent

and wouldn’t be jealous

of me because I wouldn’t

really want to

be me

whereas Peter wants

to be a woman—and

would like to be me—I think

If this archive doesn’t quite solve the enigma of Marilyn Monroe’s death, it does go deeper than we have ever been into the mystery of her life. As Lee Strasberg noted in his eloquent eulogy, “In her eyes and mine, her career was just beginning. The dream of her talent, which she had nurtured as a child, was not a mirage.”

FROM THE ARCHIVE

For these related stories, visit VF.COM/ARCHIVEDiscovery of Marilyn’s secret papers (Sam Kashner, October 2008) Marilyn and acting teacher Lee Strasberg (Patricia Bosworth, June 2003) Arthur Miller on anti-Semitism (October 2001) Arthur Miller’s forgotten son (Suzanna Andrews, September 2007) Interview with Miller (James Kaplan, November 1991) Documents excerpted from Fragments: Poems, Intimate Notes, Letters, by Marilyn Monroe, edited by Stanley Buchthal and Bernard Comment, to be published this month by Farrar, Straus and Giroux, L.L.C. (U.S.), HarperCollins (Canada and U.K.); © 2010 by LSAS International, Inc.

http://www.vanityfair.com/hollywood/features/2010/11/marilyn-monroe-201011?currentPage=all

No comments:

Post a Comment